Just a reminder that your contributions are what makes it possible for me to write and report time- and resource-consuming feature stories like this one, in which I go deep on the recent reports recommending solutions to the city’s homelessness emergency, with reporting and analysis that goes beyond the executive summary to bring you the real story. If you enjoy the work I do here, please consider dropping a few bucks in the bucket at my Patreon. And thanks.

Two consultants’ reports released last week recommended sweeping changes to the city’s policies to address homelessness, including a shift in emphasis toward permanent housing for the hardest to house, and suggested that the city’s failure to reduce unsheltered homelessness for decades is primarily a problem of priorities and math, not an intractable social conundrum.

The so-called Path Forward report by consultant Babara Poppe, along with a longer companion report by Focus Strategies, concludes that the city can “shelter all unsheltered single adult and family households [in the Seattle-King County area] within one year” by focusing its resources on “rapid rehousing” programs, rather than transitional housing; implementing a comprehensive “coordinated entry and diversion system” that focuses only on people who are “literally homeless,” rather than those who are in unstable housing and at risk of homelessness; and “reaching recommended system and program performance targets.”

The Poppe report also recommend shifting the current system of funding service providers who shelter and house the homeless, which the report says relies too heavily on the preferences of service providers, toward a “funder-driven” model in which the city of Seattle would have more direct control over which programs get funded. The new model would also require providers to disclose potential conflicts of interest and recuse themselves from funding discussions, when appropriate, and, most importantly, would require them to take on clients who need housing most desperately, regardless of factors like drug use, criminal history, and the amount of time someone has spent on the streets.

Over the past several days, I’ve read both reports in full and talked to numerous homeless advocates, council members, and service providers to get their impressions of the recommendations, which aim to house or shelter the more than 4,500 unsheltered homeless people living in King County.

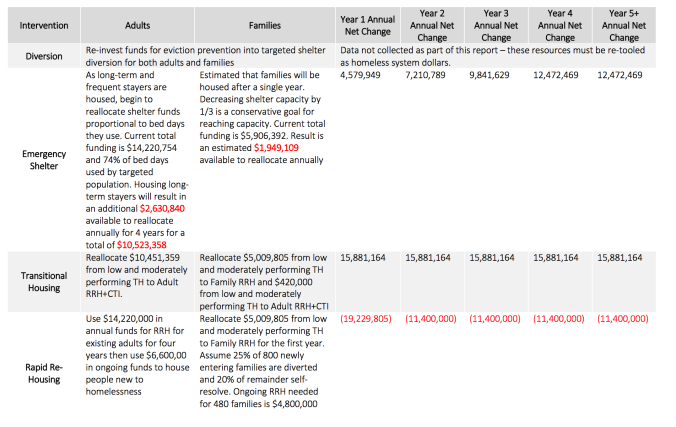

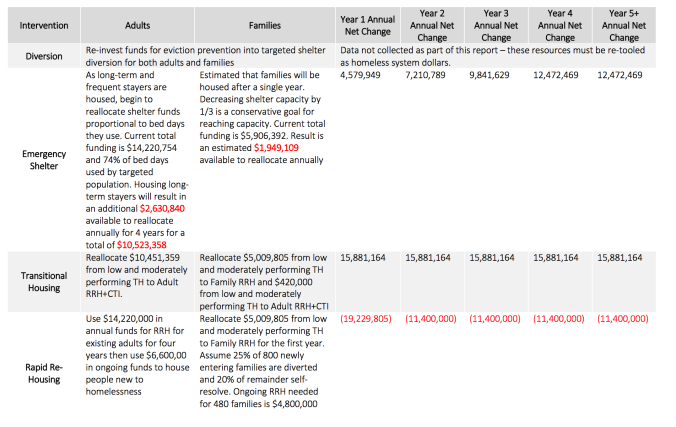

The Poppe report, along with the longer Focus Strategies report on which Poppe’s recommendations are largely based, recommends a fundamental shift in the city’s approach to homelessness that’s not just tactical, but philosophical. The biggest change the report suggests is slashing funding for agencies that provide “low-performing” transitional housing—essentially long-term, publicly funded housing one step above a shelter where the typical client ends up living for more than a year—and spending those dollars on organizations that focus on “rapid rehousing,” typically in the form of vouchers for housing on the private market that phase out over time. (These vouchers are distinct from federal Section 8 vouchers, which provide longer-term, stable housing, but for which the wait list is currently nine years.) By accelerating people’s transition from shelter to permanent housing, the report says, the city can free up shelter beds that were previously occupied by now-housed “long-term shelter stayers” for other families and individuals, getting everyone who’s currently living outdoors or staying in shelters into housing or shelter within a year. While Poppe acknowledges that “the large number of providers that will need to shift practices makes the challenge of transformation daunting,” she believes that if they do so “rapidly and with urgency,” the one-year timeline is feasible.

Others are not so sure. Council member Lisa Herbold, who worked on housing issues for nearly 18 years under former council member Nick Licata before her own election in 2015, says she’s skeptical that in the current rental market (where the vacancy rate is around 3.5 percent), enough landlords and housing providers will be swayed to provide housing to formerly homeless renters to hit the one-year target. Herbold says her “source of income” legislation, which prevents landlords from discriminating against potential tenants because their income comes from nontraditional sources, will help some, but “it’s not going to open up a whole bunch of more units, because landlords still can say that you have to have three times as much income [as your monthly rent],” Herbold says. Landlords also tend to prefer people with stable income sources, and who aren’t “high-risk” due to criminal convictions or active addiction.

Mark Putnam, director of All Home, the agency that coordinates homelessness policy across King County, acknowledges the challenge of throwing people who have been homeless for many months or years to the mercy of the housing market. But, he says, “it’s not as if at the end of nine months the client all of sudden receives a letter, and the rent assistance is over and they’ve got a $1,500 rent payment due at the end of the next month.” Instead, clients work with a case manager to help them figure out how to earn more income, get a roommate, or move into permanent supportive housing, a more expensive kind of affordable housing that provides long-term services like mental health care, addiction case management, and training. “Right now, what’s happening in many programs is that [more challenging tenants] are screened out, because maybe they’re not quite chronically homeless,” Putnam says. “It’s better to give them a chance, say, 6 or 12 months of rental assistance, than to give them nothing.”

In theory, this approach would free up a lot of money for other purposes. Transitional housing is far more expensive than rapid rehousing, according to the report—about $20,000 for each single adults, and $32,627 for each family, compared to $11,507 per household for rapid rehousing. That makes sense, since rapid rehousing typically relies on vouchers that phase out and expire within a few months, after which a person or family is supposed to “move on” to “mainstream permanent housing,” according to the report. In practice, the success of the shift to rapid rehousing will depend on the city and county’s success at finding places for people to actually live.

The report suggests tackling this problem by creating a new housing resource center to link landlords (including private landlords as well as providers that get funding from government sources) with prospective tenants, and by providing incentives to landlords who agree to take on riskier tenants, such as a “mitigation fund” to pay for any damages or eviction costs. It also suggests eliminating questions about things like criminal history and requiring providers to take hard-to-house clients even if they’d prefer to focus on easier cases.

“We have had a lot of opposition from providers on that,” Putnam says. “It took us a while [at All Home] to make that decision because there was so much provider angst about it.” Putnam echoes Poppe’s conclusion that housing providers should be required to focus on housing the most challenging cases, regardless of whether they’d prefer to take on lower-needs clients instead. “Many of the people who are living outside are screened out of our programs because of active drug use or criminal history,” Putnam says. “It’s harder, but it’s the right thing to do.”

Public Defender Association director Lisa Daugaard, whose organization runs the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program for low-level offenders, says “I’m certain that there is a strong case to be made for the existing approach,” which prioritizes people based on a checklist that measures “vulnerability,” but “I will say, that the current approach has left us pretty confident that a lot of people that we work with [at the PDA] will be unsheltered and in public.”

The report also emphasizes the need to house people who are “literally homeless” first—that is, people who are actually living outside, rather than people who are crashing on a friend’s couch, or living in an unstable family situation, for example. The idea is to get the hardest people to house (single men with addiction issues or criminal records, for example.) to move into shelter, including new shelters that allow people who aren’t sober, or who have partners, possessions, or pets, and then into stable housing, first. That, in theory, will help eliminate the bottlenecks that keep some people in shelters for years (on average, the report concludes, single adults stay in transitional housing for 328 days, and families stay an average of 527) while others languish in tents, cars, and doorways. (Pregnant women, families with children, and homeless youth will get priority over other applications if they are “literally homeless,” because they’re considered uniquely vulnerable).

After that, the report says, the system can refocus its efforts on those who are in slightly more stable housing situations, either by diverting them away from shelter or into stable housing or by sheltering them for a brief period while they find a permanent housing solution. “The impact of housing a long term shelter stayer is also not only a humane response, it will free up a precious resource that will reduce the number of unsheltered persons within Seattle,” the report concludes. In theory, refusing shelter to people with another place to go would open up quite a few beds; according to the report, in King County, only 66 percent of single adults (a category that includes couples) and 64 percent of families with children were “literally homeless.”

Emphasizing the hardest to house is a laudable goal, and it certainly reflects a shift in priorities: Instead of allowing service providers to cherrypick the people who are easiest to house, the report recommends requiring them to take the neediest first, even when that means housing people with the greatest challenges, such as addiction problems, criminal convictions, and long-term homelessness. In practice, though, there are some concerns. As council member Lorena Gonzalez noted last week, a “20-year-old women who has repeatedly been subjected to sexual assault and is not living on the street is in some ways equally vulnerable” as a homeless woman who’s pregnant, but the first woman would be dropped to the bottom of the list under the proposed new prioritization system. “It sounds to me like a values judgment about how we predetermine and predict who is most vulnerable.”

The new approach also assumes that everyone who needs housing can be housed (a housing-first principle that advocates praise), without spending much time on the challenges that simple-on-paper proposition represents. “None of what’s in the report is necessarily wrong, it’s just that it’s more complicated” than the report suggests, Daugaard says. “Measuring performance based on how many people you get into housing sounds great and is important information, but you have to have a context of how challenging are the people you’re working with? … The truth is that there’s almost an inverted relationship between the people it’s easy to work with and place in housing” and those who have the highest needs, Daugaard says.

All Home director Putnam says the shift toward harder-to-serve clients isn’t a slam on affordable housing programs, but an acknowledgement that programs that serve the homeless are distinct from those that provide affordable housing to non-homeless people, or those that work to combat poverty. (Indeed, the report itself says, “Disentangling the homelessness crisis from the housing affordability crisis in King County is critical.”) “We’re not saying that we don’t need to also have programs for the person that’s about to be evicted, but my job at All Home is strictly for people who are homeless,” PuTnam says. And within that population, too, there are distinctions. “If you’re serving people who are easy to house, that’s not a homeless crisis response so much as a affordable housing response.”

Indeed, Focus Strategies principle Megan Kurteff Schatz said last week that affordability itself isn’t an issue providers serving homeless people should be focusing on, and that placing people in housing that’s technically “unaffordable” (because it costs more than 30 percent of a tenant’s income) or less than ideal, such as a spot in a rooming house, is better than leaving them on the street. “There isn’t any reason we should be saying to people that you have to stay in shelter until we get to that day where we have enough affordable housing in the community,” Schatz said.

Poppe’s projection that every homeless person can be indoors within a year also relies heavily on new efficiencies, governance tweaks, and a few targeted new investments, rather than additional funding. (Putnam points out that Poppe was charged with determining what the city could do within existing resources, not “how much affordable housing or behavioral health services we need,” but “can we serve and house more people,” but the tone of the report throughout suggests the city, county, and providers have simply been wasteful and inefficient until now.) Currently, the report notes, “average utilization for emergency shelter was 89% for adult households and 69% for families. This suggests that there is unused capacity to house many of the unsheltered families with children in the community with the existing inventory and available beds should be prioritized for this purpose.”

However, there are two large caveats that the report does not mention: 1) The shelter vacancy rates are for all of King County, not just Seattle, and the vacancy rate for Seattle (where more homeless people live, and where most services are located) is likely lower; and 2) The vacancy rate for family shelters, which consist of enclosed units, is based on the maximum possible occupancy of each unit, meaning that a unit that could hold six but is housing a family of four would be considered only 66 percent occupied.)

This creates the distinct impression, fair or not, that the challenges of homelessness are basically a political problem, which could be solved if only leaders had the will to do it, and that the reason they haven’t is the outsize influence of fat-cat housing and service providers and the homelessness lobby. “It’s important to remember that we have the system that we have now because of public policy—it isn’t because service providers want it this way,” Daugaard says. In fact, “they have been raising this same critique for a very long time.”

“You can’t actually make all these efficient choices unless you do things that are going to make some members of the public uncomfortable , because they’re going to have to accept that people are living in imperfect circumstances and we’re going to provide shelter services to them anyway,” Daugaard notes.

One element of the Poppe proposal that hasn’t received much attention yet, but should, is that it places a huge emphasis on gathering more information about homeless individuals, which raises both privacy concerns (why, one service provider asked me, does the city or its service providers need to know whether someone is gay or straight?) and financial ones: “Proficient and comprehensive data platforms” and “dashboards” and “Homeless Management Information Systems” that track where every homeless person in the city is on a literal day-to-day basis, using a “By-Name List,” sound all right in theory, but they cost money, and every dollar that goes to new admin and overhead is a dollar that isn’t being spent on direct services and housing.

This emphasis raises significant questions, in my mind at least, about whether those non-“literally homeless” people are being left by the wayside to make the numbers (that is, the claim that everyone on the streets right now could be housed within just one year if, as Focus Strategies principal Megan Kurteff Schatz told the council committee Thursday, “the money was moved to more efficient programs”) work out. For example, a person who’s sleeping on a friend’s floor, but will have to leave next week because that friend’s landlord got wise to their unapproved roommate, or a woman whose home situation is harmful for her kids, would be considered “unstably housed,” but not literally homeless, which strikes me as a basically semantic distinction. In other words, unstable housing can quickly turn into literal homelessness.

The reports, which, throughout, contain an eye-popping amount of jargon and increasingly obtuse acronyms (TAY-VI-SPDAD, anyone?) emphasize management-theory policies such as “competitive and performance-based contracting,” “evidence-based approaches,” and “data analytics,” that jump out not just because they’re a bit eyeroll-inducing, but because removing the human element from the equation in this way, and treating homeless people (and landlords, too) as elements of a math problem that must be solved, ignores the sticky problems that make homelessness so intractable. For example, when Schatz told council members that once the new “dashboards” are up and running, service providers “should be able to produce quarterly dashboards on what kind of results that they’re getting, and you should be able to ask them, ‘Well, performance dipped over here, what do you know about that?,” I wondered briefly if she was talking about quarterly results for a for-profit corporation, or homeless men, women, and children getting roofs over their heads.

Full disclosure, if this wasn’t obvious: I have a native skepticism about any claim that a decades-old problem with many unpredictable moving parts (like, say, a person’s desire to live in the same city as their family or community support system, or a drug addict’s desire to keep using drugs) can be solved with this one simple trick, as the Poppe report suggests. (Or as Schatz put it Thursday: “You could achieve functional zero [homelessness] within five years if all the recommended changes were implemented in concert.”)

In addition to all the challenges mentioned above, there are a lot of distinctly human problems that don’t fit easily into the simple equations provided in the report, which includes no individual case studies and mostly elides complications like addiction, abuse, despair, and the desire for community that all people share, even if they’re living in a tent in the Jungle.

The Poppe report’s failure to explore addiction in any detail is particularly jarring given the fact that, according to the Focus Strategies report itself, about one in five people staying in shelters suffer from substance abuse or addiction issues. Addiction to alcohol or other drugs is not included in a list of the “root issues” causing homelessness, which, according to the report, include lack of affordable housing, lack of well-paying jobs, inequitable access to post-secondary degrees, and structural racism, among other causes. It’s an especially odd omission given the report’s repeated references to the “Housing First” philosophy, which holds, among other tenets, that people addicted to drugs or alcohol need access to housing regardless of whether they’re willing to get sober, because having a roof over your head is the most important first step before tackling other challenges like addiction. (As the report puts it, “While gaining income, self-sufficiency, and improved health are all desirable goals, they are not prerequisites to people being housed.”)

And it’s odd given the ongoing work of the Seattle-King County Task Force on Opiate Addiction, which held its final meeting Friday and will formally release its recommendations next week. Council member Rob Johnson, who has recently taken a keen interest in addressing homelessness, says “It’s important to recognize the work that the opiate task force is doing right now, and I think we’d be remiss if we were to talk about a set of strategies to address homelessness” that doesn’t integrate or acknowledge those efforts. For example, “we’ve been talking about safe consumption sites—is this part of these strategies? If it’s not, how do we think about these things from a holistic perceptive?”

Daugaard’s Public Defender Association, through the LEAD program, works with unsheltered clients who have criminal convictions, substance abuse disorders, and mental health problems that make them among the hardest to house. She notes that although the report does suggest the creation of multiple “Navigation Centers”—shelter where sobriety is not required, and where pets, partners, and possessions are allowed—it doesn’t consider the behaviors that are often associated with addiction, which might drive other homeless people out of these “everything goes” centers. “When they talk about moving from emergency shelter to 24/7, and they talk about Navigation Centers and low-barrier shelter, they do not engage with the question of, ‘should we ensure that shelter is available for everybody regardless of their behaviors? That is both an issue of the [drunk, high, or unstable] person’s willingness to go in shelter, and it’s also an issue of the person sleeping next to them in a congregate facility being willing to sleep next to a person that’s engaged in this behavior,” Daugaard says.

“Those are the kind of real application issues that make this not just a math problem. It’s also an issue of the terms and conditions under which people are asked to live.”

Fundamentally, as in all discussions about shelter, there is the question of whether people will want to move to shelter, or whether they’d prefer to continue living in the forest or on the street. Opponents of encampments and doorway sleepers often boil this down to a simple question of rights—they’re not supposed to be sleeping outdoors, therefore they must take whatever mat on the floor they can get—but like any question of human preference and choice, it isn’t that simple. People who avoid shelters have reasons for doing so, and we can’t dismiss their reasons and also live in a society where being homeless is not a crime. On the flip side, housing homeless people means putting them in neighborhoods, including areas where residents may be reluctant to welcome new neighbors whose previous home was a tent in the park.

“You can’t actually make all these efficient choices unless you do things that are going to make some members of the public uncomfortable , because they’re going to have to accept that people are living in imperfect circumstances and we’re going to provide shelter services to them anyway,” Daugaard notes.

One common reason people don’t go to shelter is that they want to choose who they sleep next to, and maybe even have sex once in a while; another is that people like to know where their home is going to be each day. It’s easy to just say “beggars can’t be choosers” and point to the cot on the ground, but it’s not really constitutional to force people to sleep there (nor is it affordable to jail them when they refuse). “Housing providers might not being a good job because they’re working with the people who are hardest to house, and it would be terrible to interpret this issue of performance-based housing as a math problem,” Daugaard says. “The people who LEAD program managers are working with—housing anybody in that group of people requires phenomenal resolve, talent, and tenacity, and it’s just important to have that context.”

The council is still reading the report and absorbing its recommendations, but the proposals did come with some urgency (a word that’s mentioned no fewer than 18 times in Poppe’s report) and a timeline: By next year, housing providers should be revising their programs based on evaluations that are arriving in the mail this week, and by 2018, if the council agrees to adopt this strategy, the city will start cutting off providers that don’t meet the performance standards outlined in the report. “Effective January, our contracts will reflect those [new] performance standards, but we will hold harmless for a year our decision making with regard to performance,” Human Services Department director Catherine Lester said Thursday.

As the council continues to dissect and discuss the report, I’ll be exploring what it means for unsanctioned encampments, whether the numbers add up, and what neighborhoods, privacy advocates, and service providers have to say about the new recommendations.

Share this PubliCola Post

Like this:

Like Loading...

Today, the city’s Human Services Department (HSD) released the results of a survey conducted by Applied Survey Research as a followup to the annual point-in-time count of people living unsheltered in King County.

Today, the city’s Human Services Department (HSD) released the results of a survey conducted by Applied Survey Research as a followup to the annual point-in-time count of people living unsheltered in King County.